Oscar Robertson during Crispus Attucks High School’s 1954-1955 championship season. Image from Oscar Robertson’s personal scrapbook. Courtesy of the Crispus Attucks Museum and the IUPUI University Library.

The Indiana Soldiers and Sailors Monument, like most monuments, has multiple meanings. For many people, gathering at the Monument is a way to come together as a community and celebrate. So when a celebration that typically occurs at the Monument is cancelled, the absence itself also sends a signal. An incident in March 1955 involving the Indiana Soldiers and Sailors Monument led basketball legend Oscar Robertson, then a high school junior, to conclude, “They don’t want us.”

In basketball-crazy Indiana, the winners of the boys high school state tournament were like princes. Traditionally, the team met their adoring public at the Soldiers and Sailors Monument for a short ceremony and then went on a parade winding through the downtown streets. Crispus Attucks High School was Indianapolis’ first championship team since the tournament had begun. Oscar Robertson naturally expected that the Attucks Tigers, like those champions he had admired before, would receive the royal treatment.

Coach Ray Crowe (center) with other teachers, administrators, and mentors at Crispus Attucks High School in June, 1956. Image from the Indianapolis Recorder Collection. Courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society.

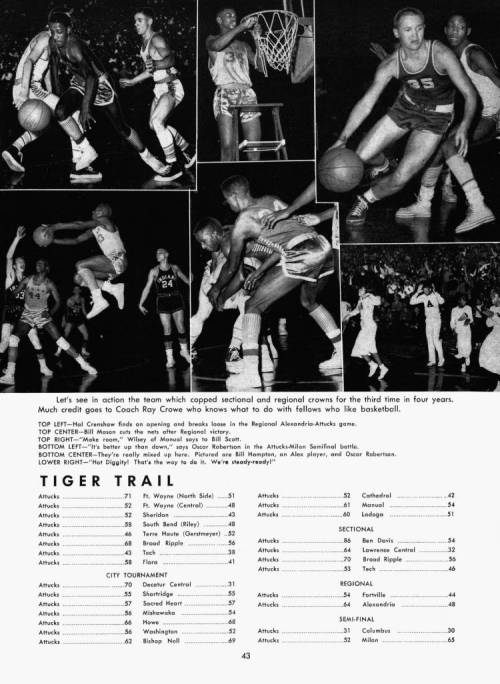

Crispus Attucks High School opened in 1927. It was established as part of the city’s effort to segregate the schools by race; all African Americans were to attend Crispus Attucks no matter where they lived in the city. Over the decades, the students and teachers made the institution an example of African American achievement. By the 1950s, as historian Aram Goudsouzian writes, the high school and its basketball team were at the center of a larger struggle for African Americans: “how to achieve black consciousness and pride while participating in a larger society on an even footing.” The Crispus Attucks basketball team began the 1954-1955 season with the goal of reaching the finals. The season before, Attucks under Coach Ray Crowe, fell to tiny Milan in the semifinals and watched as Milan ultimately won the state championship.

In 1954, the Crispus Attucks Tigers fell to Milan in the semifinals. Image from the 1954 Crispus Attucks High School Yearbook (page 43). Courtesy of the Crispus Attucks Museum and the IUPUI Library.

In 1955, however, Crispus Attucks was dominant and steadily advanced through the tournament. On March 19, 1955, Crispus Attucks met Gary, Indiana’s Roosevelt — another African American school — in the Butler Fieldhouse. Fans from all of Indianapolis’ high schools cheered the “Flying Tigers” as they defeated Roosevelt and become the city’s first boys team to win the state championship. After celebrating on the court, the team crowded onto a fire truck. Mayor Alex Clark and the city police led the procession, which included buses full of Attucks’ supporters, down Meridian to Monument Circle, where fans waited to greet the champions.

After a brief stop, during which the mayor gave Coach Crowe the key to the city, the procession went up Indiana Avenue before ending at a huge celebratory bonfire at Northwestern Park (now Watkins Park). Robertson writes in his memoir, “Something was wrong. I knew the traditional parade route. I’d seen other champions go south, take a route that led downtown and through the heart of the city.”

Crispus Attucks cheerleaders at a basketball game in March, 1955. Image from the Indianapolis Recorder Collection. Courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society.

Earlier in March, the Indianapolis superintendent of schools decided that a “mammoth victory celebration” in Northwestern Park would replace the traditional parade if Attucks won the state championship. Some fans saw the bonfire in the park as an opportunity for African Americans to celebrate in their own neighborhood, not far from Crispus Attucks. Some players were so dazzled by the win that they scarcely noticed what was happening. Oscar Robertson, however, was pained by the assumption that African Americans would have rioted if the Tigers’ fans had celebrated downtown.

“We weren’t savages. We were a group of civilized, intelligent young people who through the grace of God had happened to get together and win some basketball games. We’d just won the biggest game in the history of Indianapolis basketball.

“They took our innocence away from us.”

Robertson describes leaving the bonfire and returning home. When his father noticed his dejection, Oscar told him “Dad. . . They don’t want us.”

Instead of a parade, the Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce promised to create a scholarship fund for a worthy Attucks student. African American businesses, clubs, and fraternities hosted celebrations for the team. However, weeks after Attucks’ victory, some fans held out hope that there would eventually be a downtown parade, or at least a “city-wide banquet” but those events did not materialize. An editorial in the Indianapolis Recorder, the city’s African American newspaper, expressed disappointment at the lack of a festive “tribute” to the victors. The writer warned the city fathers that because “the city’s first state champs’ happen[s] to be a Negro Team” there was “the possibility of misunderstanding that the ‘no parade’ decision might somehow [be] connected” with the issue of racial discrimination and prejudice. For many in Indianapolis, the lack of a festive event for the deserving champions indicated that despite assertions to the contrary, Indianapolis remained divided — by race, class, and neighborhood.

The 1955 Crispus Attucks championship team with Coach Ray Crowe (third from left). Image from the Indianapolis Recorder Collection. Courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society.

In 1956, Crispus Attucks won its second state championship, and was the first boys champion to have an undefeated season. As the commentary in the Indianapolis Recorder indicated, it appeared that a new tradition, at least one relating to Attucks champions, was in place. The victory motorcade, led by the mayor, took the same route as it had in 1955, including looping around Monument Circle before heading to Northwestern Park. “The trip around the circle was only an acknowledgement of the right the Tigers, as victors, had of going that way.” The paper claimed that the police discouraged any white fans who wanted to participate in the bonfire from venturing into the park.

For the many of the players and fans, nothing could diminish the pride and excitement of Crispus Attucks basketball. Yet, in telling ways, the brief celebration at Monument Circle indicated that truly equal treatment had not arrived in Indianapolis.

—Modupe Labode

The victorious Crispus Attucks Tigers after winning their second consecutive state basketball championship, March 17, 1956. Photograph by William Palmer. Courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society.

Images from the Crispus Attucks yearbooks and Oscar Robertson’s personal scrapbook are courtesy of the Crispus Attucks Museum and Program of Digital Scholarship at IUPUI University Library. For more images, visit: http://www.ulib.iupui.edu/digitalscholarship/collections/CAttucks

Images from the Indianapolis Recorder are courtesy of the Program of Digital Scholarship at IUPUI University Library. For more images, visit: http://www.ulib.iupui.edu/digitalscholarship/collections/IRecorder